From Bank to Battlefield

The Year of Anzac

The Prince of Wales salutes as a procession of Australian

troops pass by on Anzac Day 1919. The building in the

background is Australia House, the Strand, London. The

Strand Branch of the Commonwealth Bank occupied part

of the ground floor of the building. PN-000280

The Prince of Wales salutes as a procession of Australian

troops pass by on Anzac Day 1919. The building in the

background is Australia House, the Strand, London. The

Strand Branch of the Commonwealth Bank occupied part

of the ground floor of the building. PN-000280

The landing of the Australian and New Zealand soldiers at Gallipoli on the morning of 25 April 1915 was their first military action of World War I. It was a display of strength, fortitude and courage in the face of great adversity. For a nation that had been a federal commonwealth for only 14 years this moment was a coming of age, cementing in the minds of Australia and the world the indelible image of the unfaltering Anzac spirit. The Gallipoli campaign lasted eight months and although it failed in its military objectives, it created a legacy which helped to shape the identity of the nation.

‘Knights of Gallipoli’

Anzac Day was officially named in 1916 when the Queensland Government started a movement to celebrate the landing of the troops at Gallipoli. The movement spread to many towns and cities across Australia who held services in churches or town halls, raised funds for discharged soldiers and organised marches for the returned soldiers which often included wounded soldiers who were transported in convoys of cars attended by nurses. Services were also held by soldiers fighting in France and the Australian camp in Egypt organised a sports day to mark the occasion.

In England, to counteract the bleak war news, over 2,000 Australian and New Zealand troops were taken by train to London where they marched through large crowds to Westminster Abbey for a commemoration service before continuing on to Buckingham Palace and Trafalgar Square. The newspapers dubbed them the ‘Knights of Gallipoli’.

Commemorations continue

Throughout the war Anzac Day continued to combine public mourning and commemoration with a message of imperial loyalty and national pride accompanied by exhortations to do more and give more. Each year the services and parades were usually followed by recruitment rallies in which soldiers who returned to Australia spoke to crowds of patriotism, duty, honour and self-sacrifice, calling for more young men to enlist. A special effort was also made to commemorate the day in schools with speeches, recitations and the singing of hymns. 1917 introduced a one or two minute’s silence which began to occur in some places, most often at 9 p.m. in the evening.

By 1918 Anzac Day not only commemorated Gallipoli but Palestine and the Western Front as well, recognising that the Anzac spirit first demonstrated at Gallipoli was with the soldiers in every battlefield they entered. 1918 was also the first time an organised pilgrimage occurred to the graves of Anzacs buried in England and Australia. The graves were weeded and tended and flowers or wreaths were placed on them for Anzac Day.

The first Armistice Day in 1918 saw huge crowds turn out in London to mark the occasion. The Commonwealth Bank’s London manager, Mr Campion, spoke of the heroism of Australian soldiers at Gallipoli, and in all conflicts in which they took part, and lamented that the “…greatness of the sacrifice we can only understand dimly; only as time goes on shall we realise what it meant”.

A triumphant farewell

The first Anzac Day after the armistice was commemorated with both sorrow and pride. The traditions started during the war were continued with services and marches held throughout Australia. Sprays of rosemary were worn for remembrance to show that the Australian people would never forget the sacrifice of their men. In London Anzac Day became a triumphant farewell for the Australian and New Zealand troops. 5,000 troops representing all arms of the Australian Imperial Force marched through crowd-thronged streets from the Mall to the city, passing Australia House, the home of the Commonwealth Bank in London, where H.R.H. the Prince of Wales took the salute accompanied by his brother Prince Albert. There was also an aerial display over London conducted by officers of the Australian Flying Corps and a reception for 1,500 people at Australia House in the evening. Such was the pride for Australia’s diggers, that an extra verse was added to the National Anthem, God Save the King, albeit unofficially, with the first letter of each line spelling out the word ANZACS vertically.

Reverence and remembrance

The post-war years marked a change in the way in which Anzac Day was commemorated. The often celebratory aspects of early Anzac Days faded to be replaced with a quiet reverence as people mourned for their dead and showed their sympathy for the thousands still suffering the effects of their service. There was a communal need to remember the obstacles, both natural and human, that were endured and overcome for victory to be achieved. Places of business began to be closed in the morning while the services were conducted and the services themselves started to incorporate the war memorials being built in every town and city across Australia.

By 1927, the first year in which every state observed some sort of public holiday on Anzac Day, the rituals of commemoration familiar today were beginning to be established. Flags were flown at half-mast, large memorial services were held, parades of returned soldiers marched through the streets and wreaths were placed on Anzac graves and memorials. One of the earliest official dawn services was held at the newly built Cenotaph in Martin Place, Sydney the following year, in 1928.

Within ten years these rituals were firmly established as part of the Anzac Day tradition. The advent of World War II transformed Anzac Day into a national day of remembrance for Australians and New Zealanders who served in any war or conflict.

- Armistice Celebrations

- Anzac Day

- Images of Anzac Day

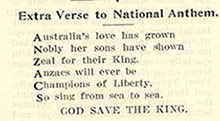

- Extra verse to the National Anthem, featuring Anzac

Armistice Celebrations

London Branch

As might be expected, old London with its 2,000 years of history, its wars, its rebellions, its fires and its plagues, rose to the occasion when the sudden blast of the “maroons” – so long the heralds of doom for many poor creatures – announced the great news.

Instantly Londoners poured out into the streets in countless thousands, and as if by magic wand had been waved, myriads of flags and banners appeared, big and little, on buildings, or carried by the excited people.

Our own Australian flag soon waved proudly on our Bank in New Broad Street, alongside the old Union Jack of the Empire. Hats waved, sirens screeched, bells rang, scratch bands started up in all directions, and enormous crowds of laughing, cheering people filled the streets throughout the length and breadth of the vast area called London.

It was hard to get on with the necessary office work, and everyone was eager to be home and rejoice with their people, so the Manager brought pleasure to the entire staff when he announced that work for the day would cease at 4pm. Still greater was the pleasure when he asked the staff to gather in the banking chamber at that hour to join in singing the National Anthem.

Failure of Might

We gathered joyfully, amid a merry hum of suppressed excitement, and then Mr Campion spoke a few quiet words amidst a solemn stillness. Quietly he reminded us of the momentous event, and what it meant to everyone in the Empire, and to the entire civilised world. He spoke of the cruel foe who had sought by Might alone to destroy our civilisation, but who had been brought to his knees by the splendid determination of our own people assisted by our faithful allies.

Though touching lightly upon the events in Gallipoli, and the vastness of the struggle of this world was, and of its horrors, compared to the puny classical wars of ancient Troy – fought in the identical lands – he brought home acutely to the many “Aussies” amongst us – in uniform or in mufti – thoughts of our sacred dead, who had made an imperishable name on those famous headlands in the Aegean Seas. And so, although we smiled and sand the National Anthem with all our hearts, behind the joy was a thought for our brave dead in France and Gallipoli, in the Balkans, or on the watery deep, who had died “for the ashes of their fathers and the temples of their Gods.”

Mr C.A.B Campion's Speech

Ladies and Gentlemen – I am sure you will agree with me that it is only right and fitting we should assemble for a few minutes today to mark this great occasion of Peace being restored once more. The day, I suppose, is the most momentous, humanely speaking, in the history of the world. Never has there been any day so epoch-making as this.

All other great events of history – the French Revolution, the Fall of the Bastille, the Napoleonic Wars, the Seven Years' War, the Thirty Years' War, the days of the Greeks and Trojans – all shrink into comparative insignificance beside the events of the last four years.

We are all too close to what has happened, and what is happening to realise the full meaning of the wonderful times we have passed through. The most striking of all our thoughts – the one standing out most prominently of all – is the heroic bravery shown by all our boys, none greater in all the ages.

The exploits of the Greeks and Trojans have been sung by Homer, and their bravery has since our earliest years filled us with the admiration and wonder. But the achievements of Ulysses and Agamemnon, of Paris and Achilles, with their bows and arrows and spears and bucklers, seem little to the brave deeds of our soldiers, advancing against and mown down by hails of shells and shrapnel.

Immortal France

And what, too, has ever equalled the heroism of our Australian boys at Gallipoli, which, as you know, is only a short distance across the straits from ancient Troy! We cannot appreciate even now the heights of the heroism to which our boys have risen, not only there, but in France, facing the Germans, who had been preparing for the war for the past forty years.

Our boys could only offer against the German cannon and machine guns, mortars and poisonous gases, their flesh and blood, but their unconquerable spirit was irresistible, and they checked the onset of the Huns, notably at Ypres and Amiens, and finally overcame them.

Our lads – so many of whom, may I say, it was our privilege and pleasure to serve from day to day in the Bank here, as well as to comfort and tend their dependents – from the mother of the “man with the donkey” to many others, these lads went over the top to meet certain death with smiling faces, cheerfully giving their lives for their country and their people.

The greatness of the sacrifice we can only understand dimly, only as time goes on shall we realise what it meant, the hundreds of thousands of lives that have been laid down, and the millions that have been maimed or scarred in this war. Today we rejoice that eternal right has at last prevailed – that right which always does prevail, but it comes specially home to us now, that although might and wrong may flourish, it is only for a season, and righteousness and justice come at last and prevail eternally.

The Joy of Peace

We rejoice that victory is given to us after all the patient suffering and endurance of these years, and I want you, before we leave, to join with me today in an expression of the joy – the chastened, abiding joy – and thankfulness we feel in our hearts that Peace has come at last, and a righteous Peace. And in these days when thrones are tottering, out thoughts turn also to our King, who has filled his high and anxious position with wisdom and prudence, and I want you to join with me now in singing the first verse of our National Anthem.

Source: Bank Notes magazine - January, 1919, Page 7

Source: Bank Notes magazine – July 1919, pages 8 & 9

Anzac Day in London

This year 5000 mixed troops representing all arms of the A.I.F., marched from the Mall to the city, passing Australia House en route. The day before was wet and cold, but as the procession started the sun shone out in welcome, and cheered everyone the whole morning.

A large contingent of the city staff viewed the show from Strand Office windows at Australia House, and had an excellent view of it.

H.R.H the Prince of Wales, standing on a dais on the pavement in front of the Bank windows, took the salute, and was accompanied by his brother, Prince Albert. Both the Princes charmed the huge crowd of sightseers by their manly and unassuming bearing, and at the close of the ceremony several Australian soldiers, not in the procession, calmly stood a few yards in front of the Prince of Wales “snapping” his photo. The crowd pressed closely in, enthusiastically cheering the young prince, and it was with difficulty the men in khaki were prevented from “chairing” him.

The High Commissioner, the Hon. W.M. Hughes, Sir Joseph Cook, and Senator Peace, stood on the dais, at the side of Sir Douglas Haig and General Birdwood. The Bank was represented by Mr Campion, the London manager, who was presented to the Prince on the dais.

The march past was an entire success, the mounted men on their superb black charges, the business-like artillerymen, and the long lines of khaki infantry and gleaming bayonets, calling forth enthusiastic cheers from the onlookers, and a vast sea of faces was visible far up and down the Strand.

There were other attractions, too, for Australian officers of the Flying Corps had their share in the ceremony. There were “angels hovering round” (Handley-Pages, with aluminium wings and Rolls-Royce engines), and one of them known as the Red Devil made the spectators gasp as they watched his daring rushes and gyrations just over the chimney tops. About a dozen aeroplanes were up, and the display was described as the finest ever seen in London.

But those who had no vision beyond that splendid body of soldiers missed a good deal. Those 5,000 men representative of nearly half a million of healthy young fellows, who had volunteered to help in the great fight for freedom. They stood for the heroes of Gallipoli, Villers-Bretonneux, and of Mont St Quentin, the latter a great natural fortress defended by acres of wire and thousands of German bayonets, but which fell to a handful of Australian bombers: the taking of the first-named by our men constituting the turning point of the war.

Then men also represented a vigorous people, who, 11,000 miles away, were loyal to our King and Empire, and who had made great sacrifices to preserve the freedom won for the Empire by their kinsfolk in this older land in the days gone by.

Seen this way, and remembering that never before in London had 5,000 armed Australians marched past the heir-apparent to the throne of the greatest Empire the world has ever seen, it was an impressive and memorable occasion.

While we Australians feel proud of it all, we should not forget that we are not “the only pebbles on the beach.” This fascinating old London many times saw the superb cohorts of Rome march through her streets, and no doubt along this very Strand; at any rate, through ancient Watling Street, but a short distance away.

Doubtless that great Englishman, King Alfred, rallied his men near by in his fights against the Danes.

The Knights Templar of the twelfth and later centuries must have often marched past where he stood, for their General Headquarters were but a stone's throw away, just inside Temple Bar, where their interesting church still stands. Like our boys, they travelled far to fight for what they believed was a righteous cause, and many of the brave fellows after a good fight left their homes in a far distant land.

Then the warriors of that great Queen, Elizabeth, often trod these very streets, and soldiers of our late beloved Queen Victoria marched down the Strand to the city on their return from the Crimea, or other distant parts of the world, where they had gone - like our lads - at the call of duty.

But while one rejoiced at the splendid showing made by the bronzed fighters, one could not keep back thoughts of the Silent Company who were sleeping on Gallipoli, in France, or Egypt.

For every living man on the present march, twelve had given their lives (we lost 60,000 killed during the war).

In the evening the High Commissioner and Mrs Fisher gave a reception at Australia House, which 1,500 people attended, including many of the senior staffs of the city office and Strand branch.

Like the daylight ceremony, the evening function was a brilliant success, the magnificent rooms of the building and the marble pillars and staircases showing to perfection.

Source: Bank Notes magazine – September 1919, page 12

Extra Verse to National Anthem

Australia's love has grown

Nobly her sons have shown

Zeal for their King

Anzacs will ever be

Champions of Liberty

So sing from sea to sea

GOD SAVE THE KING

Please email us if you are a relative or have further information that you would like to share.