From Bank to Battlefield

Managing the Bank in Times of War

Governor Denison Miller

Sir Denison Samuel King Miller was the first Governor of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia and played a significant role in the establishment of central banking in this country. He had a unique burden of responsibility. Only a few years after setting up the Commonwealth Bank as a commercial concern, Denison Miller was faced with the challenge of having to also support the financial needs of the government in a time of war.

The extraordinary demands placed on him during the First World War spanned both his professional and personal life. At the same time as he was shaping a national institution, three of Sir Denison's four sons enlisted. The eldest was killed on the Western Front in 1917. And, of course, the Bank's staff were also serving on the battlefields. Sir Denison was renowned for his personal attentiveness and pastoral care, and his concern was returned with such gratitude and admiration that a number of Bank officers wrote to him from the battlefield, even while they were under threat of death.

Recalling Sir Denison's role in the financial management of the war effort, The Sydney Morning Herald reported: ‘… Sir Denison Miller played a part the value of which cannot be assessed in monetary terms. He was in finance the Government's chief of staff, director of strategy, intelligence and publicity bureau. Every Administration, whatever its political doctrine, acknowledges its debt to this just and provident steward.’

On the home front, the First World War presented Australia's banks with two major problems: how to raise enough money to pay for the war effort, and how to finance Australia's international trade under war conditions. Sir Denison Miller and the Commonwealth Bank took the lead in solving the banking side of both these matters by issuing and managing loans that ended up providing more than half the total spent on the war. The 10 war loans raised £250 million.

Progress of

Commonwealth Bank of Australia

Reprinted from

THE BANKERS’

Insurance Managers’ and Agents’

MAGAZINE.

(LONDON.)

September, 1918.

In August, 1914, at the outbreak of the war, three of Mr. Miller's sons volunteered for service. The eldest, Lieut. Clive L. Miller, Australian Filed Artillery, served through the whole of the Gallipoli Campaign. He was killed in action at Messines on July 4, 1917. In private life, Lieut. Miller was a member of the Sydney Stock Exchange. Another son, Gunner John K. Miller, Australian Field Artillery, after returning to Australia in 1915, came over and has been in France since December, 1916. He has been wounded twice and gassed once, and is now ordered out to Australia.

On the outbreak of war, Mr. Kell's elder son, Lieut. Ralph Kell, enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force as a private. He was in the original landing at Gallipoli, and after the Gallipoli Campaign was promoted to Lieutenant; he was wounded in France, and after promotion to Captain was returned to Australia, where he has resumed his duties with the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney.

Mr. Campion's eldest son, Dr Rowland B. Campion, Captain, R.A.M.C., crossed over to France with the First Expeditionary Force, under Sir John French, on August 8, 1914, and served at Mons, St. Quentin, the Marne, and the Aisne, after which he proceeded with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force in 1915. He is now in charge of the Auxiliary Hospital at Alexandria. Captain Rowland Campion has been mentioned in Despatches, and especially commended for his services.

The second son, Gifford (Wadham College, Oxford, and the Inner Temple), was in King Edward's Horse during his three years at Oxford, and is now a Captain in the Royal Field Artillery, having seen much service on the Western Front, including the Somme, Messines, and Ypres. He sustained a severe shrapnel wound at La Bassée;, and was mentioned twice in Despatches for distinguished service. Captain Gifford Campion is an M.A. of Oxford University.

Dr Oliver St. Leger Campion is a Lieutenant in R.A.M.C., and is at present serving in Africa. The fourth son, Austin, after serving with King Edward's Horse, has been for several years a Lieutenant in the Second Battalion of the Welsh Regiment, and is at present on the Western Front. The fifth son, Jasper (of Hertford College, Oxford), served as a Lieutenant in the Duke of Wellington's West Riding Regiment, then commanded a Trench Mortar Battery for a year on the Western Front, and was later in command of the 439th Siege Battery, which he took out to France.

This record of service would be difficult to beat; nevertheless we believe it to be symptomatic of what is general, not only in the Commonwealth of Australia, but in all parts of our Empire.

The Bank also played a big part in financing the export trade. Before the war, the export of commodities had been handled by wool-broking firms, grain merchants and others. But not only did the war limit the available shipping, it also upset the established means of payment and varied the demand for Australian products in Britain. The solution, which was financed by the Commonwealth Bank (under the watchful eye of Sir Denison), was to pool commodities, arrange finance for producers and control exports. As a result, by the end of the war the Bank was firmly established as the Australian Government's banker and its agent in most financial matters. The physical evidence of its evolving stature was best expressed by the imposing Head Office, opened in 1916 in the heart of Sydney.

After the war, the Governor's high standing in the community was consolidated as repatriation, immigration and land settlement became the key issues of the day. Such was his status in the public eye, there was even some discussion following his death as to whether he should be the first and last Governor of the Commonwealth Bank, with one commentator suggesting that some other title, such as President, be created for his successors ‘so that the people down through the centuries to come will think of Sir Denison Miller as always being with them as Governor of their Commonwealth Bank assisting in the shaping of Australia’s great Destiny’.

The Governor Abroad

In early 1918, the Bank's first Governor, Denison Miller, was specially requested by the Prime Minister of Australia, The Rt.Hon. Billy Hughes, to accompany him to England to advise on financial matters at the Imperial War Conference of Dominion Prime Ministers, which took place in June and July of 1918.

They sailed from Sydney on the 26 April 1918 aboard the R.M.S. Niagara, bound for New Zealand and Vancouver. Once in Vancouver, they travelled overland to New York, departing this city on the American transport ship the Adriatic on the 5 June 1918, as part of a convoy of eight troopships. The departure had been delayed by some 24 hours due to the spotting of an enemy submarine in the Atlantic Ocean.

Arriving in London on the 16 June 1918, they were met by The Rt.Hon. Andrew Fisher, Australian High Commissioner, and the Bank's London Manager, Mr Charles Campion. Among the many invitations he received during his time in London, Denison Miller was guest of honour at the Royal Colonial Institute Luncheon, on the 26 July 1918. He also attended the opening of Australia House by King George V on the 3rd August 1918 (the King had laid the foundation stone for this building in July 1913). Governor Miller's son, Gunner John King Miller, who was wounded in action in France in April 1918 and was convalescing in England at the time of his father's visit, was also present at the official opening.

At the invitation of the A.I.F., Governor Miller also spent a week in France, during which an inspection was made of field arrangements for paying troops. He also visited hospitals, the Red Cross, the Y.M.C.A. and other sites and institutions, both there and in England.

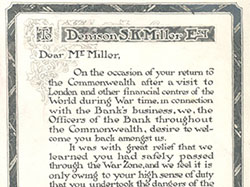

Denison Miller returned to Australia on the 13 November 1918, two days after the Armistice had been declared. He received a most enthusiastic welcome from the staff of the Commonwealth Bank and a reception was held in his honour to officially congratulate him on his safe return. At the function, the Governor was presented with an illuminated address, in which the hope was expressed that he would ‘…long remain at the head of this great Institution, which has flourished and progressed under your guiding hand.’

During the proceedings, Denison Miller gave a moving account of his time abroad, and this was reproduced in the staff magazine, Bank Notes, in January 1919.

The High Commissioner of the Commonwealth of Australia

Requests the honour of the company of Denison Miller Esq

On the occasion of the Official Opening of Australia House by His Majesty the King

On Saturday, August 3rd at 11.30 am

R.S.V.P., The Secretary,

Opening Ceremony,

Australia House,

Strand, W.C.2.

To Denison S.K. Miller Esq

Dear Mr Miller,

On the occasion of your return to the Commonwealth after a visit to London and other

financial centres of the World during War time, in connection with the Bank’s

business, we, the Officers of the Bank throughout the Commonwealth, desire to

welcome you back amongst us.

It was with great relief that we learned you had safely passed through the War Zone,

and we feel it is only owing to your high sense of duty that you undertook the

dangers of the voyage during the progress of the War. May we, therefore, on behalf

of the Staff throughout the Commonwealth, take this opportunity to extend to you a

cordial welcome home, and also express the hope that you will remain at the head of

this great Institution, which has flourished and progressed under your guiding hand.

Yours Sincerely

on behalf of the Staff

(Signed below)

| N.S.W. | QUEENSLAND |

| James Kell – Deputy Governor | Manager, Brisbane |

| E.W. (Edward William) Hulle – Manager, Sydney | Manager, Bundaberg |

| Mark Young – Inspector, Sydney | Manager, Maryborough |

| Hugh Traill Armitage – Chief Accountant | Manager, Rockhampton |

| Assistant Manager, Sydney | Manager, Toowoomba |

| Manager, Albury | Manager, Townsville |

| Manager, Broken Hill | S. AUS. |

| Manager, Canberra | Manager, Adelaide |

| Manager, Dubbo | Manager, Pt. Adelaide |

| Manager, Lismore | Manager, Pt. Augusta |

| Manager, Liverpool Depot | Manager, Pt. Pirie |

| Manager, Newcastle | W. AUS. |

| Manager, Orange | Manager, Perth |

| Manager, Tamworth | Manager, Fremantle |

| Manager, Wagga Wagga | Manager, Kalgoorlie |

| VICT. | TASMANIA |

| Manager, Melbourne | Manager, Hobart |

| Manager, Ballarat | Manager, Launceston |

| Manager, Bendigo | NEW BRITAIN |

| Manager, Geelong | Manager, Rabaul |

Page 1

His Observations and Experiences

America and Europe in War Time.

“The members of the great English banks and the Australian banks in London received me very favourably because they recognised that the Commonwealth Bank was now a very powerful factor, not only in the finances of Australia, but in the finances of the world.”

Mr Denison Miller sounded this note of pride in the service when acknowledging in a gracious speech the presentation made to him by the staff on his return from his business tour abroad.

“In the opinion of the London market and of the other banks, we occupy a prominent position to-day,” the Governor added.

“At the invitation of the Royal Colonial Institute, I was the guest of honour at a luncheon, the object of which was to hear from me how the Commonwealth Bank was progressing. Those gathered around the tables were surprised to hear what the position of the Bank was.

They learned for the first time that the Bank was founded in Australia without any capital, and without a Board of Directors, and that the profits were not distributed to anyone, but were kept in the reserves of the Bank. There, however, was the proof, and to those who heard the story of the development of this great institution it appeared remarkable. They were deeply interested, and I was warmly congratulated upon the Bank's success. I welcomed the opportunity to trace the Bank's progress, step by step. And I know you all share with me my pride in this young financial giant whose destiny we are guiding.”

The Governor paid a tribute to the Deputy-Governor.

“I knew when I went away" he said, "that he would be supported by the whole staff. For some time I personally engaged every officer of the Bank, particularly in the early stages. I very carefully scrutinised the training and upbringing of all. The importance of this must have been apparent to everyone. It is gratifying to know that you have all proved loyal officers, and I thank you all for what you have done while I was away.

It is really a great pleasure to me to hear the letters from branches read, and I very much appreciate the kindness with which they were written, and the remarks made by Mr. Kell and Mr. Hulle. We have really one of the most remarkable institutions in the world. That is only possible if the Bank is run in a businesslike way, and I knew there would be no danger with Mr. Kell while I was away, and the staff would do their work loyally, because I do not carry on the Bank; it is the staff who carries on the Bank, and it is due to their care and the way they do their work that the Bank is successful. I am only the controlling influence to direct how things should be done, but it is really the staff themselves who have the credit of the popularity of the Bank, and I fully recognise this.

There is no one more pleased than I am to-night as to the future prospects. As Mr. Kell said, as long as we get good seasons we can handle all the other things. We have had three or four years of war trouble. Why can't we get through peace? There ought not to be much trouble. We cannot help little troubles and little drifts that come along but Australia cannot do anything but succeed. The only thing that can effect is bad seasons.

I thank you, the Australian staff, but I must also thank the London staff. I felt always that you were doing your share. We have a large number of men away and when they come back their places will be ready for then. I do not want to turn anybody away. I want to keep all the staff permanently, and to do this we have had to go a little short, otherwise there would have been the necessity of sending some away. As you know, for some time past we have not taken any men of military age on the staff. The girls have done their work well, and entered into the sphere of banking and become a permanent part of it. I think the other banks will probably also keepa great many of their lady clerks on.

Now, the London staff had a very much more trying time than we had. They were there in the front in the firing line. They were working night and day, and there were not enough senior men to train what help we could get. I think they have done wonderfully well. At the chief office we have a staff of about 200, mostly girls, who knew nothing about banking. Mr. Campion, the manager, has worked night and day. At the Strand Branch, where we occupy the whole floor of Australia House, where most of the soldiers’ accounts are kept, we have a large staff under Mr. Pinhey, and they have all done the same. They have stuck to work because it was necessary. In London we took on a number of temporary hands, but as many of those as I can possibly do with I will keep on.

Here in Australia the most important thing for us to do is looking after repatriation and the returned soldier. By-and-bye I think they will soon settle down to the ordinary life. To them is due our attention.

Mr. Kell, Mr. Hulle, ladies and gentlemen, I thank you all very much for your welcome home, which I very much appreciate. (Applause.)

I wish to propose a hearty vote of thanks to the Deputy-Governor for presiding at this meeting to-night, and to tell you (I thought Mr. Kell had already done so) the whole of the staff is granted a 10 per cent bonus.” (Applause.)

Page 2

The Staff Welcome

There was a great gathering at Head Office on Monday, 23rd December, when the officers and staff extended a welcome home to the Governor, Mr. Denison Miller, on his return from a business trip abroad on behalf of the Commonwealth Government.

After many wearisome delays, the Governor was released from quarantine on Saturday, 21st December, and on the following Monday evening advantage was taken of the occasion to bid him welcome home again to our midst.

Head Office, which has every facility for a function such as this, threw itself wholeheartedly into the event. Detail arrangements were in the hands of a sub-committee of the Patriotic Club, which carried out its duties as efficiently as ever.

The hall was tastefully decorated, to which it lends itself readily, a large "Welcome Home" sign over the stage being the central feature. Palms and flags lent a touch of colour to the scene, to say nothing of the pretty dresses of the charming ladies of the staff and visitors.

Mr. Miller was accompanied by Mrs. Miller, and his son John K. Miller, who has returned invalided from the front. Miss Tennyson, and Miss Blanche Miller, and Mr. and Mrs. A.C.Y. Miller.

Most married officers were accompanied by their wives, and there were upward of four hundred assembled in all. The Governor, on arrival, was given a rousing reception, all being upstanding, and singing "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow," followed by three good Australian cheers.

The short musical programme contributed to by Miss Hosie, Mr. H. Brown, Miss Taylor, and the Hon. R. B. Orchard, won hearty applause. Mr. James Kell, Deputy-Governor, presided, and read letters and telegrams of greeting from the branch managers in the various States of the Commonwealth. On behalf of the staff, Mr. Kell extended to Mr. Miller a hearty welcome back to Australia.

On rising to speak Mr. Kell was accorded a generous round of applause, a sure indication of the good feeling which exists between him and the staff. This must have been as gratifying to the Governor as to the Deputy himself.

Deputy-Governor's Speech

“Your temporary absence,” said the speaker, turning to the Governor, “has served to impress upon us more fully than ever the magnificent work you have done in connection with establishing this great institution of ours, and the splendid service you have rendered to your country by your advice and financial counsel.

Before our Governor left Australia,” said Mr Kell, “no name stood in higher esteem and regard throughout the Commonwealth than that of Denison Miller. It is very gratifying to us, too, to know that the leading men on the other side of the world have a similar opinion of his capacity as a banker and his sterling qualities as a man. Having tried to fill Mr. Miller's shoes for a few short months, I fully realise that all these good things that have been said by people in Australia and on the other side of the world are absolutely true. I am in a position, perhaps better than anyone, to know the good work which Mr. Miller has performed.

After the way he has been feted and treated by the titled people on the other side, we are pleased to find that he has returned to us just the same cool-headed, kind-hearted man who left us a few months ago.”

When Duty Called

“When Mr. Miller left Australia the voyage to England was beset with many dangers, but he made the trip in the interests of the Bank and the country. We are glad he did, so that the experience he has gained in contact with the financial men on the other side will be of great assistance in the future conduct of the Bank, and will be very valuable in the affairs of the nation. Many post-war problems will have to be solved, and I am sure Mr. Miller's advice will be freely accepted and freely given when solving these problems.

To-day the staff of the Commonwealth Bank is equalled by none in Australia, and during Mr. Miller's absence it has worked with the greatest enthusiasm and zeal. The members have worked uncomplainingly long hours, and some of our members have kept at it until they had to give up under the doctor's orders. The senior officers, Mr. Hulle and the others, have worked with me with the one object, and that was the good of the bank. They have made my task comparatively light, but all the same I am quite sure no officer in the Bank is more pleased to see the Governor back than I am.

Mr. Miller, on behalf of the staff, I would ask you to accept this small memento of our affection and esteem."

Mr. Kell then presented the Governor with an artistically prepared address in album form, a copy of which is reproduced in this number.”

The Loyalty of the Staff

Mr. Hulle said it gave him very great pleasure on behalf of himself and the Sydney staff to say they were very glad to see Mr. Miller back again safe and sound after what has been a very perilous journey. “This trip,” said Mr. Hulle, “as you know, was not taken for pleasure, but in the interests of an institution - an institution which was founded by our Chief, nursed by him in its infancy, and organised in such a way that it has now assumed the position which places it in the very front rank of banking institutions of the world.

I can assure our Chief of the loyalty with which the Head Office staff worked during his absence, and always with a feeling of contentment that they were doing their bit at a critical time when other men abroad were doing theirs. In stating what is a recognised and self-evident fact that the best man was selected for the Governorship of the Commonwealth Bank, I hope you will permit me to say also that no better choice could have been made in the Deputy-Governor than the present one. I would like to tender for myself and staff, our thanks to the Deputy-Governor for the very kind consideration he has shown us on every occasion.”

The Governor's Reply

In the speech accompanying the remarks at the head of this report, the Governor gave an interesting and graphic account of his experiences travelling to and from England, and of his impressions of the French battlefields.

Mr. Miller said:

“Mr. Kell, Mr. Hulle, fellow-officers, and friends here, I have heard so many nice things about myself to-night that I really wonder whether I have come back from the front. If I had I am very much afraid I would be pretty well spoilt. It is a very great thing to me that you appreciate what I have done, and I think perhaps you would like to know something of what we did from the time we left Sydney till we got back, what has been going on, what the business was that we went for, what the visit meant, and a few of the things we saw.

As you know, Mr. Mason has acted as my secretary all through, and to him I wish to tender my very best thanks for the very able manner in which he has carried out his duties.

We started out in the Niagara, and we were escorted by a destroyer. There was a scare at the time, and the aeroplane officers got busy, as it was thought there was a raider about somewhere, and seaplanes were flying overhead. You may not have known at the time. We were escorted part of the way across to New Zealand by the destroyer, and the first day out it was very interesting to see this. (Mr. Hughes and Sir Joseph Cook were on board.) The destroyer raced past us, and left behind a screen of smoke, which completely hid us from view, and gave us an indication of what a smoke screen was in battle.”

Page 3

Across the Pacific

“We got to New Zealand, and picked up the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Hon. W. Massey, and the Treasurer, Sir Joseph Ward. We got safely across to Vancouver, and there our party was split up, some going by way of Seattle to see ships being built for the Australian Government. Mrs. Hughes launched one ship. We were shown over a very interesting shipbuilding yard, where there were 9,000 men employed, and there was another yard a little further down the Bay where there were 7,000 men employed. We saw ships in the course of construction, in every phase, from the putting down of the first piece of steel till completion. These ships were steel ships of 8,800 tons each, and were completed in 53 days. Now, that seems a wonderful thing to do. A fortnight after this they were away carrying on the business for which they were constructed. That was only one yard of many in America in which they were doing the same thing.

We came across the American Rockies, and Mr. Hughes and myself were invited to ride on the electric locomotive, which took us over the divide. At the top the altitude was 6.300 feet; we rode for 100 miles up and down on an electric train over this altitude, and for 400 miles the line was electrified. The whole of the train weighed, I believe, 3,300 tons, and the cars were steel and the carriages were steel; the cars held 60 tons each of goods, which will give you an idea of what this line was like. Going up the incline we had used all the electricity that was made, and when we began to descend on the other side the engine made more electricity going down than it could consume.”

What America Did

“We got to New York, and I had the opportunity for two or three days of visiting the prominent bankers there. Then we went to Washington, and were received by the British Ambassador, and had an opportunity of meeting the various Ministers of the Cabinet. They told me confidentially what America was doing. I can tell you a few things of what they said now the war is over. This was on the 25th May, and at that time things were not looking too well for the Allies. The attitude of the Americans was: “They said America did not come into the war till now, but now we are in we propose to do all we can to help the Allies. We are all intent, and we feel that it is up to us to do our share of the war. We think that France has been bled white, and Great Britain is hanging on by the skin of her teeth. We are going to try and repay something of what the Allies have done for America. We are sending 200,000 a month, that is, 50,000 men a week.”

We were timed to leave New York on a certain day, and when we got down we found the boat was not ready to leave. Papers came out in headlines. ''Two Submarines off New York," "The Port of New York Closed." Then next day papers came out in large headlines again, “Convoys held up in America.” What Will America Do?” “Were They Frightened of Two Submarines?” That day we left. There were eight ships in the convoy, and we passed out through the narrow channel, a British man-o'-war first. The ship we were on carried 2,600 troops, and a few privileged passengers like ourselves. As we went out through this passage a little patrol boat with about 10 or 12 men on board lined up alongside each ship. These boats carried allied depth bomb throwers. These bombs were used if a submarine was near, and proved effective anywhere within a radius of 200 feet. Three or four destroyers and two or three seaplanes were escorting us, and a big thing they called 'a blimph,' a type of airship.”

Long, Long Days

“We got up north towards Iceland, and then we were so near to the North Pole that at one time it was only night for two hours.

It impressed us very much to see the care with which the Admiralty convoyed us; the

destroyers, the battleships and the transports were all British, we were escorted

from the time we left America till we arrived in England. One of the most wonderful

things was what a wireless man on his boat told me —that they received instructions

how to steer every four hours from the Admiralty Office in England by wireless.

We reached England, and were met by Mr. Fisher, the High Commissioner, and Mr. Campion, the manager of the Commonwealth Bank in London; we were taken to the Savoy Hotel.

“Influenza was raging, and I was the only one of the whole party who escaped it. There were very few deaths at that time. We were soon in the thick of what was going on in London, and we gave our attention to seeing what our London and Strand Offices were doing. Then we visited a number of the Australian camps, and saw our soldiers. I organised new branches at three or four bases, which were found necessary.”

Page 4

Post-War Problems

“As to the war, if America could send 200,000 men a month and Great Britain find the ships, it would not be very long before the Germans would be down and out. I then gave them till March, 1919, but America coming in so wholeheartedly helped to finish the thing quicker. Instead of arranging finances for a long war, I soon saw the proper course was to turn my attention to demobilisation, and I spent a good deal of my time at the pay office and the demobilisation department.”

Visit to the Front

“Before I left England I took the opportunity - at the invitation of the A.I.F. - of going over to France, being escorted by the Chief Paymaster, Lieut.-Colonel Evans, and spent a week in France, examining the various activities - War Chest, Red Cross, various hospitals, aerodromes, pay offices, and saw the whole organisation of the battlefield. We were provided with what they call the ''white" pass, which had to be viseed by the French General and War Office. A special military car had been arranged for us to travel about in, but the morning we got to Boulogne we received telephone orders that the car was not to leave the town, as a stunt was on, and all cars were likely to be required.

At Abbeville we were met by Colonel Murdock and Major Horden, Red Cross Commissioners. We had a Red Cross car, which took us wherever we wanted to go, a Red Cross officer driving. We spent a couple of days in Paris, interviewing bankers and agents there.

We went to Rouen, and saw the 1st Australian Hospital. From there we went to Amiens, which was in occupation of soldiers only. The place was a desolate ruin. The city had been one of the brightest and gayest. Formerly they had a population of about a quarter of a million of people, but now a large part of it was wrecked beyond description, and hardly a soul to be seen. This was our first real view of the pitiless devastation of the war.”

Where the A.I.F. Stood

“We went along to Villers-Bretonneaux, and the towns from there on were shell-torn and shattered. Formerly they were towns and cities. They were now a picture of despair. On our way we saw a big gun captured by the Australians. The length of the barrel was 86feet, and it was 15inches in diameter, and the barrel itself had three different bands of steel round it, and these appeared to be 15inches themselves. The breech of it had been blown out. Apparently either a charge had exploded in breech or the Germans had done it wilfully. The gun was fixed in a position 40km from Amiens, and it was trained to throw these enormous shells into that city. The Engineers told me that they must have been fired only about five or six shots before it was blown to pieces.

In Paris they have an 11inch gun which was captured by the Australians some months before, complete. There was the gun itself and six trucks to carry the ammunition. This gun was mounted on the railway trucks, with a railway engine attached to draw it to the required position. We hope to get it back to Australia for exhibition. We went up through Peronne. At the time we were attacking Cambrai pushing the Germans back. We met the 4th Division coming out of the line. They were big sturdy Australians, swinging along. They cheered and waved their hands to us. We were told we would see other troops coming into the line, which we did. An attack was to be made on a certain morning, and we saw by the papers before we left France that the attack had been successful, and the objective taken. It is a matter of note that the Australians had taken every post they were directed to attack, and have never lost a position once they took it.”

On to Pozieres

“Going on to Pozieres we saw the Australians' graves. In the cemetery where rest our gallant dead they have erected a fine cross to their memory. The Germans had not touched the graves at all. You could see little chips off some places apparently from bullets, but there was no wilful damage.

We returned to England, and went to Scotland for a trip, and saw the Fleet. The morning we arrived there we found the "Australia" was suddenly called out of port. We spent two or three days in Scotland, and while there we went up to the Trossachs, and had a look around. Mr. Fisher took us in his car to see the shipbuilding on the Clyde, and as we were passing through Dumbarton we came to a street that we could not get past, as there was such a crowd of people. There were two Australian soldiers putting out a fire on a tramcar, and the rest of the people were looking on, cheering, and blocking the traffic.

In America we had the opportunity of visiting the whole organisation of the Red Cross. The head of the Red Cross took me in hand and showed me everything. When we got to England I went into the whole of the organisation of the Red Cross there. I will say this, that what I saw really opened my eyes. The Red Cross, as you know, attend to only the sick and wounded. With the fit men they have nothing to do. They keep a complete record of the parcels sent to the prisoners of war. They could not get in touch with the prisoners of war in Turkey, but all in Germany were supplied with parcels containing articles of clothing and food. In France we found the Red Cross very active. I cannot say too much for the organisation and care that Colonel Murdoch has displayed in the management of the Red Cross, and he is very ably supported by Major Hordern, who is in charge in France, and deals with the actual work at hospitals and in the battlefield area.”

The Wonderful Y.M.C.A

“The Y.M.C.A. is the most wonderful factor of all. They look after the soldiers well in every way. When Australian soldiers arrive in London on leave they are met at the railway station and taken in motor cars to the A.I.F. Headquarters. From there they are taken across the street to the War Chest, where there is a comfortable meal waiting for them for 1s, or a bed for 4d, with baths and everything. Every morning, no matter whether it has been slept in by the same man, every sheet and pillow-case is taken and washed. The soldier’s fare is fixed. They can have meat twice a day. A civilian can only have meat four times a week. If you cut your meat ticket in two, you can have meat eight times a week. (Laughter.) Food is not only very scarce, but very expensive. You have to save up meat tickets before you can buy a chicken. Even if you keep chickens you are not allowed to eat them unless you produce your meat ticket.”

The Women of England

“The women of England have done wonderful work. I do not give any higher praise to any women than to the women of Australia, but the women of England are all doing something for the war. One sees women on trams, in fields working, and women driving motor cars and motor lorries. Women are all in uniform. The women in munition factories wear suitable uniforms, girls on buses wear leather boots up to the knee and short skirts. If a woman does not belong to some organisation she might as well stop at home, for nobody will speak to her. Everybody is doing something for the war. One of the principal accountants in England is up at the War Office managing one of the departments, and does not see his own business from one week end to the other. It is the same with hundreds of men.

The Y.M.C.A. have little huts all over the place. We saw fifteen ourselves. They are neat little buildings at corners of the park, and one is in Trafalgar Square. They have a rest room. The soldiers go in, say where they have come from, and are asked where they want to go to, and are directed to accommodation. The Adelphi Theatre was taken over by the Y.M.C.A. to accommodate soldiers, and is fitted up as a restaurant and hostel, and entertainments are continually going on. A great many of them want to go into the country. There are lists of hosts and hostesses, and they keep a record of these places. The boys are looked after from the time they get into London.”

Page 5

Paris Leave

“In Paris they have taken a very large hotel, which will accommodate I do not know how many. I think 355. The boys get what they call 'Paris leave.' The Y.M.C.A. meet them at the stations, and escort them to this hostel. They accommodate all they can, and have a list of other places to send them to. They try and get the boys to pay in advance - 42 francs (that is, 6 francs for bed and breakfast for seven days, a very reasonable price) - and as they all must have £10 in their pay-book before they get leave, they have the rest of the money for spending as they please. During this winter, instead of about 2,400 on leave, they expected about 9,000. There is nothing more terrible than to have a lot of soldiers coming out of the line with nowhere to go. That is the work the Y.M.C.A. is doing. Some people say they make money out of it; they charge for what they give. The Australian soldiers would sooner go to a place where they had to pay a reasonable price than they would go to a place where they got it for nothing. They would sooner go to the Y.M.C.A. and pay their money than have it given for nothing. They will not take charity. As far as the Y.M.C.A. are concerned, they are doing work that no one else can do. The Australian has to look after himself. If we do not help to look after him he is left on the street. No matter what it cost, the Y.M.C.A. are willing to find the money, and they deserve the fullest support from the Australian public, which I have no doubt will at all times be forthcoming.

Now, about the boys themselves: it makes one feel proud of being an Australian to hear what is said of their conduct. In the Anzac Buffet, War Chest, and Y.M.C.A. huts, we were told that they had never had to turn an Australian soldier out of an entertainment for drunkenness or misbehaviour.”

Ravages of Influenza

“When we sailed for home the boat we travelled in was the Olympic, of 49,000 tons. The night we went out was very stormy. Submarines were reported outside. Our boat being very fast, there was not much danger. The submarine was not very effective if the boat made more than 15 knots an hour. We got over to New York all right, and stayed there in the midst of the influenza epidemic. At Washington there were 371 deaths the day we arrived. To keep the places free from the disease all the employees of banks and other institutions were turned out of buildings twice a day while they were aired. Most of the people serving behind bars and fruit shops, etc., wore masks. Windows were taken out of cars to permit thorough ventilation. Theatres were closed. Although the elections were on, crowds were not allowed to congregate. It was the same going across Canada. In some States we had to wear masks ourselves. The people were dying in thousands all through Canada and America. I forget the total, but a great many more were killed by influenza than by the war.

The principal trouble at Auckland was landing the Auckland passengers. The quarantine station was occupied by German internees. After discharging the passengers we found we were short of coal, then we were short of seamen and engineers; the passengers fired and stoked the ships themselves. Otherwise we would have been in Auckland still.”

An undated photograph of the Royal Mail Ship (RMS) Niagara. As part of his wartime visit to North America and Europe in 1918, Denison Miller sailed to New Zealand and Canada onboard the Niagara.

PN-004087

Guests attending the Royal Colonial Institute luncheon in London on the 26 July 1918. Denison Miller was guest of honour at this function, at which he spoke of the many achievements of the Commonwealth Bank, at home and abroad.

PN-001452

A Family Affair

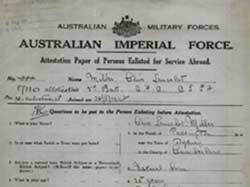

Lieutenant Clive Miller

(Governor Denison Miller's son)

When war broke out in 1914, three of Governor Denison Miller's sons volunteered for service: two of them returned. The eldest, Lieutenant Clive Miller, served through the whole Gallipoli campaign but was sadly killed in action at Messines, Belgium, on 4 July 1917.

Although Governor Miller was probably the only Commonwealth Bank officer to receive a message from the King and Queen consoling him on the death of his son, his loss was simply one of many suffered by staff at all levels and in all locations of the Bank.

Of course a number of Bank officers and members of their families survived the horrors of World War I, including Denison Miller's two other sons John and Ernest.

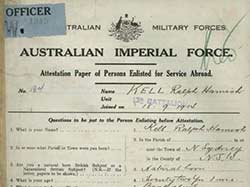

Captain Ralph Hamish Kell

(Deputy Governor James Kell's son)

Lieutenant Ralph Hamish Kell, who was later promoted to Captain, was the elder son of Deputy Governor (later Governor) James Kell, and lived to tell the tale of the original landing at Gallipoli as well as other campaigns. A banker like his father, Kell had enlisted less than six weeks after the outbreak of war in September 1914. He served at the Gallipoli Peninsula, in the Middle East and in France, taking part in the Australians' first major action on the Western Front at Pozières. Kell was wounded twice in the left arm, the first time in August 1916 at Pozières and the second at Gueudecourt in February 1917 during the Battle of the Somme.